Debt Digest | Uncapping the Payroll Tax Won’t Save Social Security

Links & Fiscal Facts

Gentle reminder if you haven’t yet registered: Cato will be hosting the Social Security Symposium: A Global Perspective on May 9th from 8:45AM ET to 2:30PM ET. You can join us for breakfast and lunch in-person in Washington D.C. or follow along online. Hope you’ll tune in!

Here are this week’s reading links and fiscal facts:

Foreign aid package would add $95 billion to the deficit. On Saturday, the House passed a series of supplemental appropriations bills that provide emergency funds to Ukraine, Israel, and the Indo-Pacific region. Credit to Reps. Brecheen (OK-R), Hern (OK-R), and others for submitting amendments to rescind certain funds as pay for. The unobligated funds left in the pandemic era State and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund, for example, could more than offset the proposed new spending. Without offsets, new emergency spending contributes directly to the nation’s mounting debt problem at a time when fiscal forecasts are gloomy, threatening America’s long‐term fiscal and economic security. The Senate is scheduled to vote on the House package later today.

Uncapping the payroll tax won’t save Social Security. Manhattan Institute’s Brian Riedl demonstrates that eliminating the Social Security tax cap (thus taxing all earned income) would only close half of the program’s long-term funding shortfall, as shown in Figure 1. If the tax cap is eliminated in 2024, Social Security would return to running deficits by 2029, merely five years later. Riedl also questions the rationale behind raising taxes on today’s workers to finance the benefits of today’s retirees, who are “the wealthiest age group of Americans in history.” As Riedl puts it: “pledging that today’s workers will pay any tax necessary to ensure that even multimillionaire seniors can continue to receive benefits far exceeding their lifetime Social Security contributions is neither progressive nor sensible.” Better reform options will reduce the unsustainable cost growth in Social Security without raising taxes on working Americans; see here, here, and here.

Debt monetization, aka printing money to support government deficit spending, leads to inflation. “‘U.S. fiscal stimulus during the pandemic contributed to an increase in inflation of about 2.6 percentage points in the U.S.,’ three economists with the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis estimated last year. A big reason […] is that the trillions intended to stimulate the economy were essentially created out of thin air, "borrowed" from the future. “Debt issuance is inflationary when forward-looking agents believe that newly issued government debt is only partially backed by future taxes,’” writes Reason’s J.D. Tuccille.

As Dominik Lett and I argue, “With entitlement spending growth driving a worsening fiscal picture, the US could enter a new period of fiscal dominance” where the Fed would primarily serve the funding needs of the Treasury instead of controlling inflation. Congress should rein in the unsustainable growth in Medicare and Social Security spending, instead of trying to borrow the nearly $80 trillion of unfunded obligations these programs are facing. Failure to stabilize the growth in the debt could put the Fed between a rock and a hard place, driving debt monetization that “can lead to hyperinflation and economic ruin,” as we’ve written.

Curbing spending is necessary to avoid a fiscal crisis. In his recent paper, “A Case for Federal Deficit Reduction,” Cato’s Ryan Bourne argues that federal budget deficits must be reduced to avoid a fiscal crisis and economic instability. According to Bourne, historically high deficits, coupled with rising interest rates, exacerbate the already unsustainable federal debt, heightening the risk of a severe fiscal crisis. “If investors were to lose confidence in the federal government’s ability to repay its debts, they would demand sharply higher interest rates [...] A sharp, large surge in bond yields would feed directly into a higher deficit, with extra borrowing then driving up yields further in a so-called fiscal doom loop,” writes Bourne. To avert this scenario, Bourne suggests adopting a comprehensive deficit reduction package, which would include “forward-looking reforms to age-related entitlement programs, elimination of wasteful or economically harmful government programs, and pro-growth tax and regulatory reforms to ease the burden of the fiscal adjustment.” As I’ve written previously, the US may go ‘bankrupt,’ at first gradually, then suddenly.

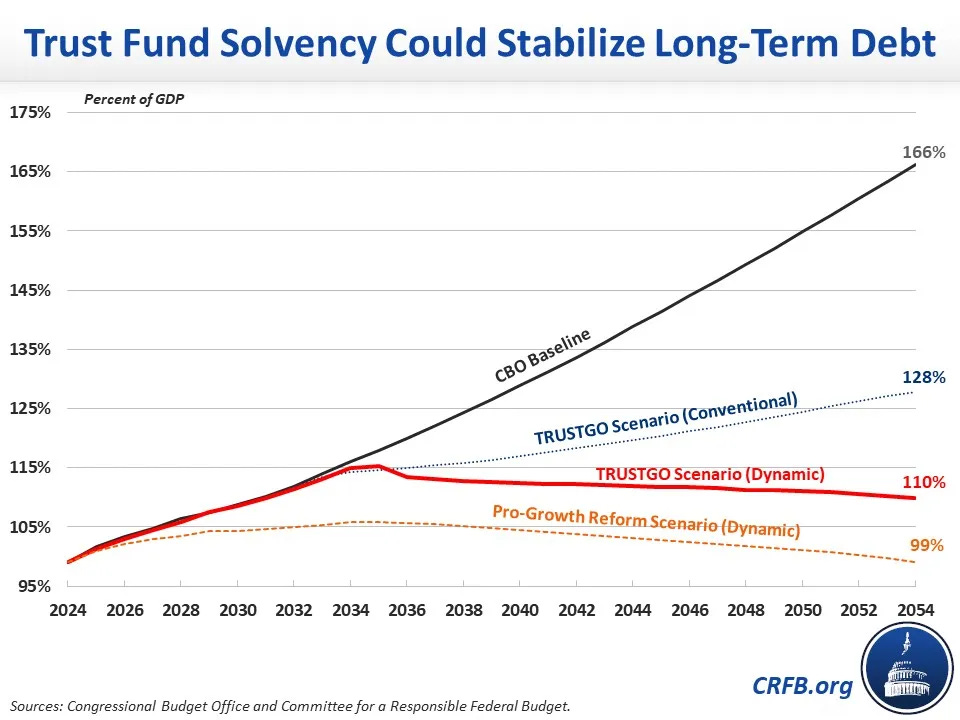

Trust fund solutions could stabilize the unsustainable US debt. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB) demonstrates how allowing automatic benefit cuts to take place, after the depletion of the highway, Social Security, and Medicare trust funds, would affect long-term debt-to-GDP projections. The CRFB's analysis suggests that scheduled benefit cuts would lower the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) forecasted debt from 166 percent to 128 percent of GDP by 2054. Additionally, the CRFB explains: “We estimate this lower spending and debt would accelerate long-term economic growth and stem the rise in interest rates. These dynamic effects would lower debt-to-GDP by another 18 percentage points to 110 percent of GDP.” The CRFB also predicts that “thoughtful pro-growth trust fund solutions in advance of the trust funds' insolvency dates'' could reduce debt-to-GDP to 99 percent (see the chart below). With elected officials unlikely to allow for 23 percent benefit cuts for Social Security beneficiaries and 11 percent benefit cuts for Medicare’s hospital reimbursements, Congress should pave the way for thoughtful entitlement reforms by empowering an independent BRAC-like fiscal commission. More on that here.

Student loan forgiveness is a bad idea. “[W]e estimate the plan could cost $250 billion to $750 billion, depending on how the additional cancellation is designed [...] these policies would put upward pressure on inflation and interest rates by supporting stronger demand, and much of the benefits would accrue to high-income and highly-educated Americans,” writes the CRFB regarding the Biden administration’s latest student loan cancellation plan. In addition to the direct costs of such a policy, Cato’s Clark Neily and Neal McCluskey have highlighted the broader consequences of mass student loan forgiveness: “There’s also the effect mass cancelation would have on already astronomical college prices. Basically, it would send the message that if debt holders complain enough, a future president will simply wipe out a bunch of their debt [...] This would bode ill for future students because there is powerful evidence that colleges raise prices as students get access to more taxpayer funding [...].”

Social Security Symposium: A Global Perspective | May 9, Washington, D.C. & Online

·Social Security Symposium: A Global Perspective May 9, 2024 8:45 AM - 2:30 PM EDT The Cato Institute, 1000 Massachusetts Ave, NW, Washington, D.C. and **Online** Breakfast and Lunch will be served. As we approach the 90th anniversary of the US Social Security program in 2025, and as the program’s trust fund is projected to be …