Here are this week’s reading links and fiscal facts:

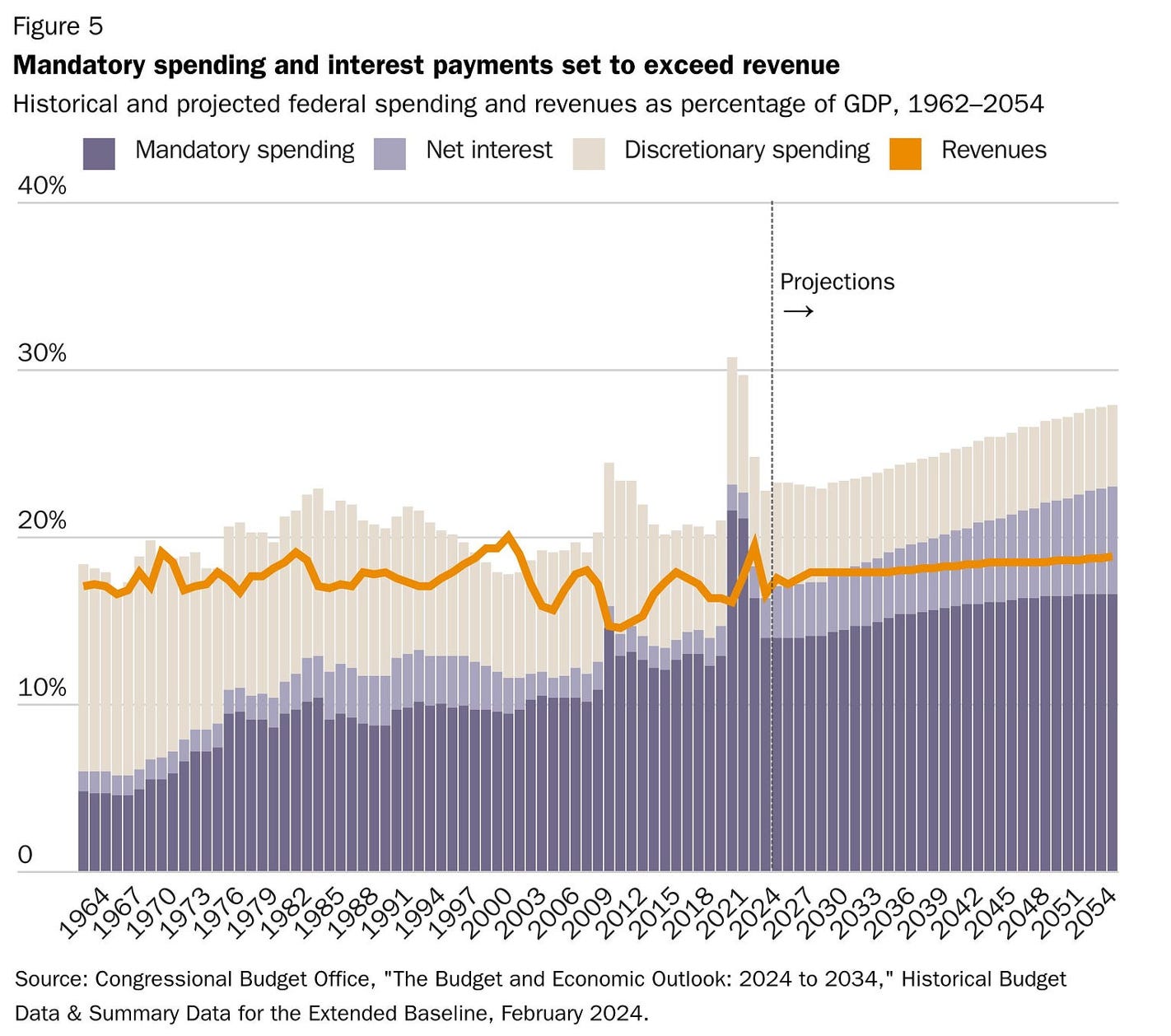

The US tax system is increasingly progressive. As Cato’s Adam Michel explains, “The top 10 percent of income earners pay more than 60 percent of all federal taxes and 76 percent of income taxes, shares that have been increasing over time.” With that said, the United States remains a low-tax country compared to other wealthy nations, a fact that benefits American workers and employers. However, given persistent US budget deficits, a low US tax environment may not last. Figure 5 illustrates how mandatory spending on programs like Social Security and Medicare, along with interest payments, is projected to exceed all revenues this year. This means that all discretionary spending would be deficit-financed. For more on the growth of old-age benefit programs and their impact on the budget, see here.

Budget delays should have consequences for the President. Kurt Couchman notes that at the beginning of February, President Biden once again failed to submit a budget request to Congress on time. The President is required to present the executive budget to Congress by the first Monday in February. However, President Biden’s submissions have all been delayed, with delays ranging from 31 to 116 days. In response, Senator Joni Ernst (R-IA) and Representative Buddy Carter (R-GA) introduced the “Send Us Budget Materials and International Tactics In Time (SUBMIT IT) Act,” which would prohibit the President from delivering the State of the Union (SOTU) address without submitting a budget proposal beforehand. As Boccia has written previously, both Congress and the Executive could benefit from stronger incentives to deliver budgets on time.

Government deficits threaten market stability. Pacific Investment Management Co. (PIMCO) warns that persistent US government deficits may trigger higher premiums on long-term debt. “While term premium remains slightly negative, bond investors are wary of another climb that in turn could push 10-year yields back toward 5% and spark broader financial market tumult.” Importantly, rising premiums would mean higher interest costs, which could pose a threat to fiscal stability. For more on how rising interest costs could precipitate a fiscal crisis, see here.

Debunking damaging Social Security myths. Manhattan Institute’s Brian Riedl challenges ten pervasive myths hindering Social Security reform. For example, Riedl explains that highlighting Social Security’s looming insolvency is not a scare tactic but a legal reality, as beneficiaries face across-the-board benefit cuts of 23 percent as soon as 2033, if Congress fails to act. Propagating this and other myths slows down reasonable debates about reform solutions. As Riedl rightly points out, “Demagoguing Social Security reform will not make its funding problems disappear.“

Lessons in monetary policy. Boccia recently visited Savannah, Georgia and nearby Tybee Island for a Liberty Fund seminar on monetary economics, covering ideas from Madison to Warburton. As Cato’s James A. Dorn explains, “Warburton’s concern with the ambiguity of U.S. monetary law may have been expressed more than 75 years ago, but it is still relevant today.” Mercatus’ Scott Sumners writes, “The current dual mandate is ill-defined and allows each side of the political divide to argue whether money is too easy or too tight.” Dorn concludes, “A look back at Warburton’s thoughts on monetary control and the Fed can shine a light on the need for sound theory and credible institutions that help reduce uncertainty and anchor expectations regarding long‐run price stability.”

America’s worsening demographics. As the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB) chart below shows, the US faces a demographic problem. By 2060, nearly one in four Americans will be an older adult. A growing elderly population combined with slowing birth rates means there are fewer taxpayers on the hook for covering the rising cost of old-age program beneficiaries. In the case of Social Security, benefits are designed to grow faster than inflation, compounding the long-term budget problem. Slowing excessive benefit growth can reduce Social Security’s fiscal burden without implementing economically harmful tax increases.