States Should Be Able to Opt Out of Social Security—Here’s How to Do it

State alternatives to Social Security won’t work without strong guardrails

As Social Security faces looming insolvency, various alternatives are being proposed to fix the problem. One provocative example comes from Jason Sorens, who calls for state governments to opt out of Social Security and Medicare and replace them with state-managed alternatives. Allowing states to opt out of Social Security is an idea worth discussing, but without safeguards, it risks repeating the same fiscal mismanagement and underfunding that have plagued both federal entitlements and many state-run pension systems.

Advocates of state-based alternatives argue that opting out of federal programs would be beneficial to federal taxpayers and could encourage innovation. Sorens himself notes: “Big-government states might want to continue Social Security and Medicare as large, costly, pay-go systems, but they would still have the incentive and the means to reform these programs for fiscal solvency.” Unfortunately, public pension system management in these same states shows strong incentives to underfund benefit promises.

If state alternatives to Social Security are poorly designed, they could threaten state fiscal health and create incentives for state policymakers to seek federal bailouts when their systems fail—undermining the very premise of decentralization and innovation. For states to responsibly design alternative retirement systems, they must learn from past experience—not only at the federal level but also from their own mismanagement of public pension systems.

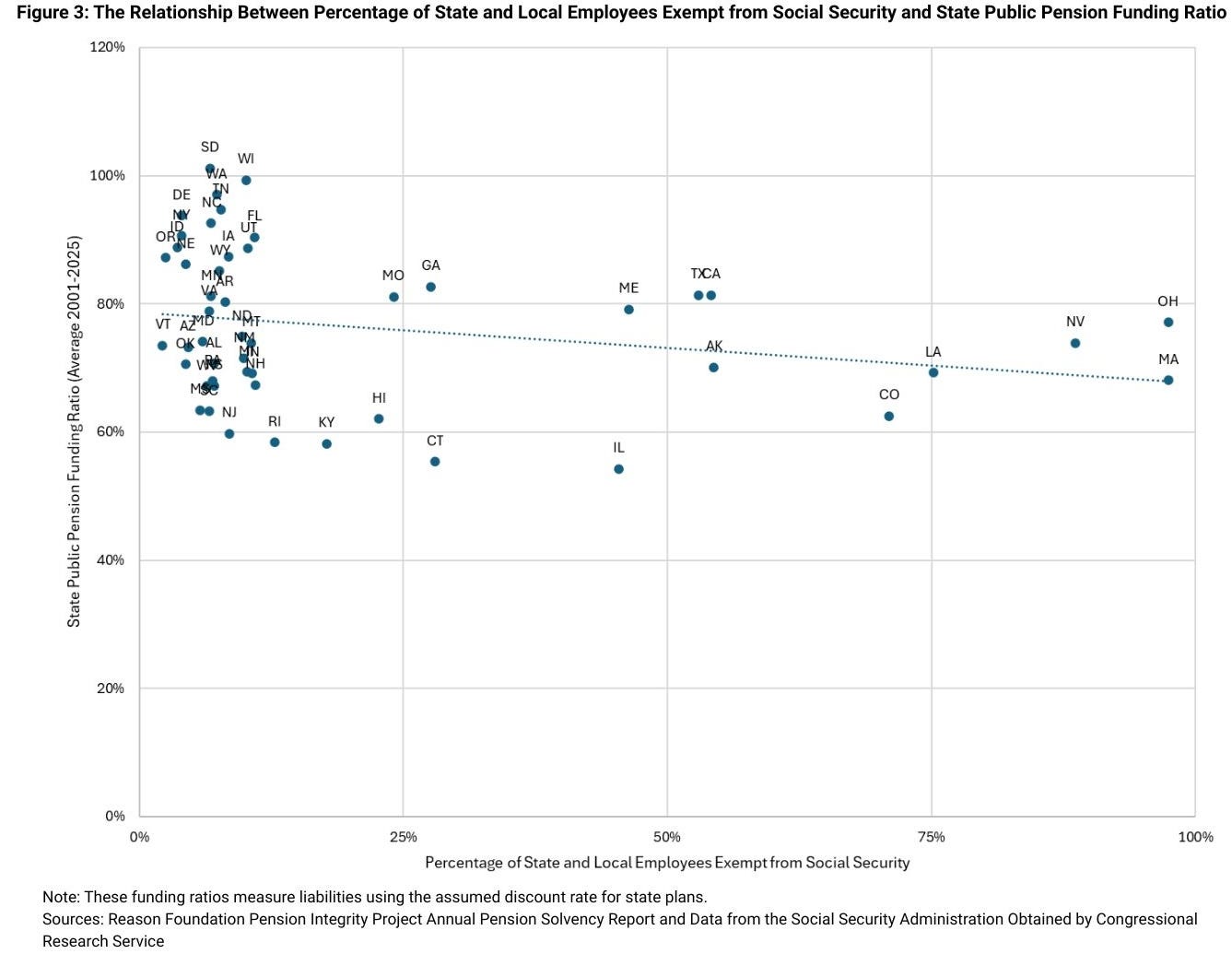

This piece examines whether states that exempt large shares of public employees from Social Security achieve better retirement outcomes with their own pension systems. Specifically, I look at the health of state and local public pension funds in relation to the share of employees exempt from Social Security. Initial observations show no strong correlation between exemption and stronger pension funding, suggesting that merely opting out is no guarantee of fiscal prudence.

If states are going to assume responsibility for retirement security, they must adopt meaningful guardrails that protect taxpayers. Those guardrails can be taken from the successes of public pension reform, such as the numerous states switching to defined contribution retirement systems as well as Wisconsin and Maine.

Exempt from Social Security but Not from Pension Trouble

When Social Security was first established, the federal government exempted state and local government employees from paying into and receiving Social Security in the hopes of avoiding a constitutional challenge over whether the federal government could impose a payroll tax on state and local public employees. Over the post-war period, Congress expanded coverage to these employees. Under current federal law, if a state or local public pension meets a “Safe Harbor” standard, those employees are exempt from paying into and receiving Social Security benefits.

This “Safe Harbor” standard requires that these pension plans must give public employees an annuity at retirement that is equal to the value of the Social Security benefit a public employee would have received at retirement if he or she was paying into Social Security.

Examining how public pensions are funded compared to Social Security offers an interesting comparison. One stark difference between public pensions and Social Security is that public pensions are designed to be pre-funded. This means a public pension plan should receive enough contributions to pay all the retirement benefits promised to those employees during the years they are working and earning benefits. Social Security, on the other hand, is designed as a pay-as-you-go system, where current workers are taxed to pay for the benefits of current retirees.

At face value, a public pension system appears stronger than Social Security because it does not depend on current workers outnumbering current retirees, making it more fiscally responsible than Social Security.

However, requiring a plan to be pre-funded does not guarantee solvency or protect it from political meddling. The weighted average state public pension funding ratio between 2000-2025 was 78.6 percent. For context, the American Academy of Actuaries recommends that public pension plans have a 100 percent funding ratio (although others argue that the 80 percent funding ratio to match private sector plans is sufficient). Striving for a 100 percent funding ratio also reflects the legal protections of public pensions, specifically that states cannot back out of promised benefits. Regardless, the average public pension funding ratio over the past 25 years falls short of either benchmark.

Additionally, public pension investment plans have increased risk in their investment portfolios to chase yields and have been hamstrung by social investment strategies (most recently ESG). These gimmicks leave funds vulnerable to market downturns and allow liability growth to rapidly outpace asset growth.

Do Social Security Exemptions Correlate with Better Funding?

Last year, the Congressional Research Service published data on the share of public employees exempt from Social Security in 2021. Their map is recreated in Figure 1.

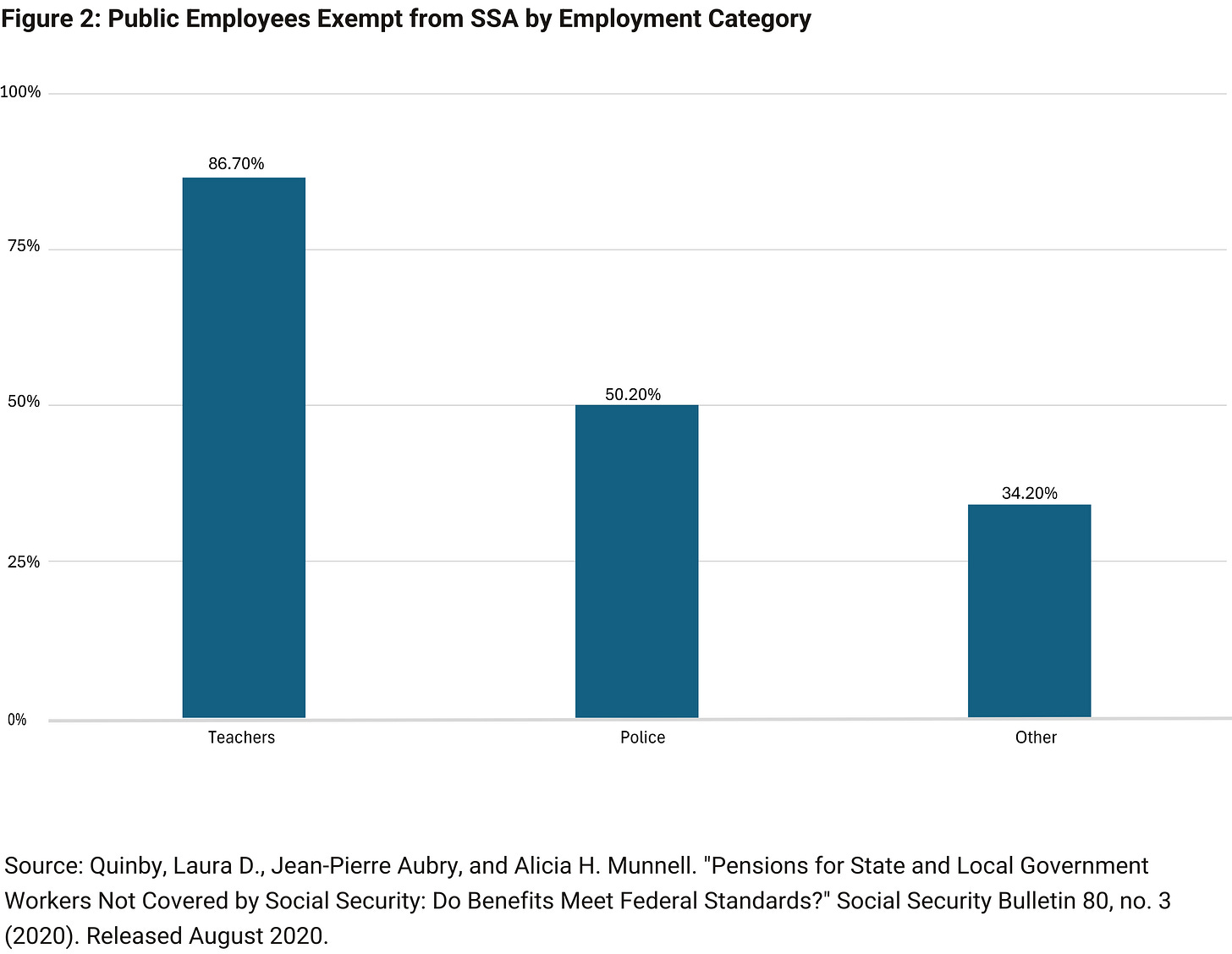

A 2020 study surveyed state and local government employees exempt from Social Security. Among the public employees surveyed, nearly 90 percent of teachers, more than half of police, and just over 34 percent of all other government employees were exempt (Figure 2). Teachers provide a unique case, whereas among public employees they are most likely to meet the Safe Harbor exemption.

It is unclear if these exemptions make a state more fiscally responsible. Figure 3 compares a state’s public pension funding ratio (total pension assets divided by total liabilities expressed as a percent) with the percentage of state and local employees exempt from Social Security. I take the average state pension funding ratio from 2001-2025 for each state. This is shown in Figure 3.

Unfortunately, this simple relationship does not tell us much. Most states have fewer than 25 percent of public employees exempt from Social Security, yet outcomes vary widely—from well-funded systems like South Dakota (101 percent funded) to severely underfunded ones like New Jersey (60 percent funded). An opportunity for further research could examine this relationship while controlling for states with a significant number of public employees in defined contribution retirement plans (i.e., 401(k)).

Why Constraints Matter

While many factors influence public pension funding (i.e. plan design, pension investment returns, and contribution policies), Social Security exemption does not seem to provide a strong incentive to keep public pension funds fully funded. The State of Illinois, with over 45 percent of state public employees exempt from Social Security, is an egregious case. Despite influential public sector unions as well as a constitutional amendment guaranteeing public pension benefit payments, Illinois pensions are some of the worst funded in the country. The State suffered 21 credit downgrades from 2009 to 2017 and unfunded pension liabilities were cited as a major reason for these downgrades.

Ohio, a state where nearly all public employees are exempt from Social Security, protects pension benefits through state statute. Currently, the state has over $64 billion in unfunded pension liabilities and a funding ratio of 77.4 percent, just below the 80 percent minimum funding ratio recommended by some.

If state policymakers do not have strong enough incentives to fully fund public pension systems for a concentrated and influential group of public employees, a public retirement system for all state residents (a much larger group with more diffuse interests) wouldn’t be managed any better without proper constraints.

Furthermore, another reason to require proper constraints is the risk of state policymakers lobbying the federal government for a bailout when funds go insolvent. During the economic downturn in the Spring of 2020, state policymakers made several requests to receive unrestricted federal aid with no repayment plan. One such example was Illinois State Senate President Don Harmon’s request for $42 billion in additional federal funds, including $10 billion specifically for underfunded state and local pensions. Additionally, then-Governors Hogan (Maryland) and Cuomo (New York) requested $500 billion in “unrestricted federal assistance.”

Lessons from Sound Pension Reform

If the proper constraints are not put in place to stop a federal bailout of the states, states running their own Social Security system have a strong incentive to gamble with investments, underfund benefits, and then request a federal bailout when these gimmicks fail. Of course, the best safeguard against this would be an explicit ban on a federal bailout of the states. Although it is probably impossible to ex ante guarantee no federal bailouts, a bailout ban would encourage greater policy competition among the states as well as reduce the moral hazard of states enacting risky policies (such as chasing investment returns to keep pension funds solvent) because federal taxpayers will not be there to cover their losses. Federalism thrives the less the federal government meddles in state and local affairs.

Although public pensions face their own issues, over the past twenty years states have made steady improvements in reporting thanks to updated government accounting guidelines. In addition, funding ratios have held relatively stable since the Great Recession (even by the more prudent estimates) although those funding ratios have yet to return to pre-2007 highs.

Aside from egregious cases such as Illinois, many state legislatures have proven capable of tackling the pension problem better than Congress’s handling of the Social Security problem. For example, several states automatically enroll new hires into defined contribution plans (such as a 401(k) plan). If states are to enact a Social Security alternative, enrolling all citizens into a defined contribution retirement system would be the gold standard. This would allow citizens to save and invest retirement funds in an account they owned that no one else could touch on or draw from (the opposite of Social Security). Even if the state were to provide matching retirement contributions to a 401(k), it would cost significantly less than either a state managed defined benefit pension or a replica of Social Security.

If a state were to enact a defined benefit system, such as a traditional public pension, the system’s success would be determined by the strength of the system’s institutional constraints. Possible constraints on these state-wide retirement systems could include cost and risk sharing measures such as the one enacted by the Wisconsin public pension system. These reforms included the requirement that public employees contribute half of the annual contribution instead of a fixed percentage of payroll. In 2016, Maine policymakers pursued a series of reforms which implemented variable contribution rates, a type of risk-sharing plan, for their state pension system, greatly improving pension funding. Additionally, these systems should be designed to be prefunded instead of replicating Social Security’s “pay-as-you-go” system, which depends upon those paying into the system outnumbering the number of retirees.

Alternatively, if states choose to have their own separate retirement system, they could enroll residents in an individual retirement account, such as a 401(k) and provide matching contributions. This would allow individuals greater freedom to choose how their retirement dollars were saved and invested. It would also prevent political meddling (i.e. ESG) with retirement savings, which has been rampant among public pension funds.

Allowing states to opt out of Social Security is a serious idea worthy of discussion. While implementation would be challenging, it is not impossible. What matters most is ensuring states avoid past mistakes by adopting meaningful guardrails that ensure long-term sustainability and protect taxpayers from unfunded obligations.

Thomas Savidge is a Research Fellow at the American Institute for Economic Research.

Follow on Twitter/X: @thomas_savidge.