Debt Digest | Reaching a 3% Deficit Target With a BRAC-Like Commission

Links & Fiscal Facts

Here are this week’s reading links and fiscal facts:

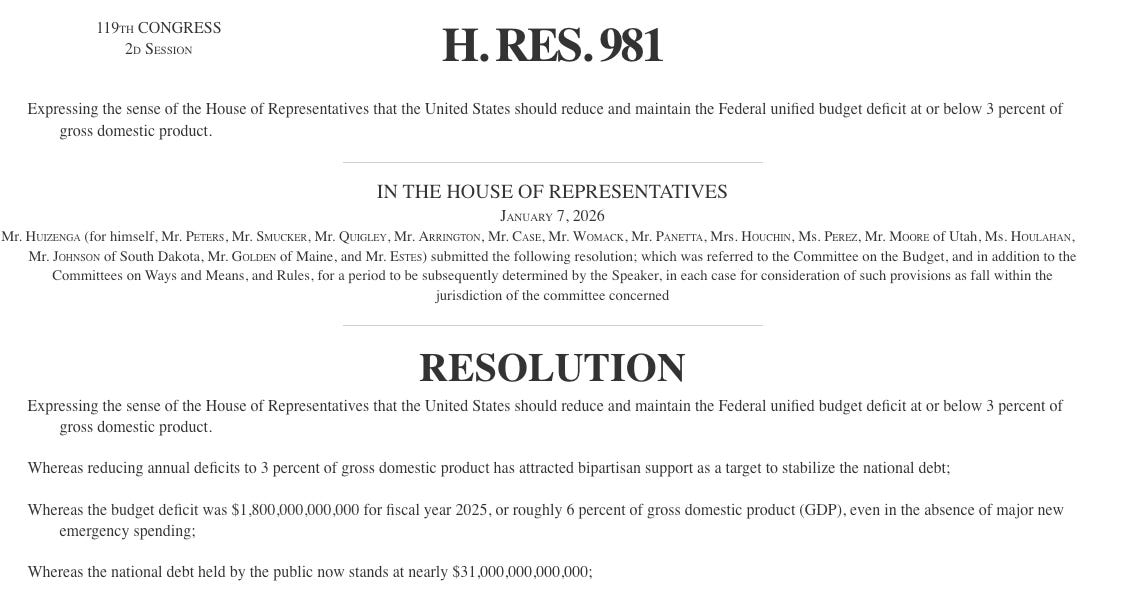

Growing 65+ population fuels increased Medicare and Social Security obligations. In their new demographic outlook the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) “projects that the U.S. population will become older, on average, over the 2026–2056 period. The number of people age 65 or older is projected to rise through 2036, growing at an average annual rate of 1.6 percent. That rate is faster than the average growth rates projected for younger groups.” This demographic shift means more federal spending on Medicare and Social Security with less revenue from younger workers’ payroll taxes (as seen in the falling ratio in the figure below). As Boccia and Thakur write, “Medicare’s structure, including the program’s fixed eligibility age, turns longer lives into higher public spending by automatically financing additional years of medical consumption.” For Social Security, Boccia and Lett explain, “Social Security faces increasing financial pressure due to changing demographics, from increasing life expectancies for program beneficiaries to a decline in the number of workers financing the program’s spending, combined with absolute benefit increases.”

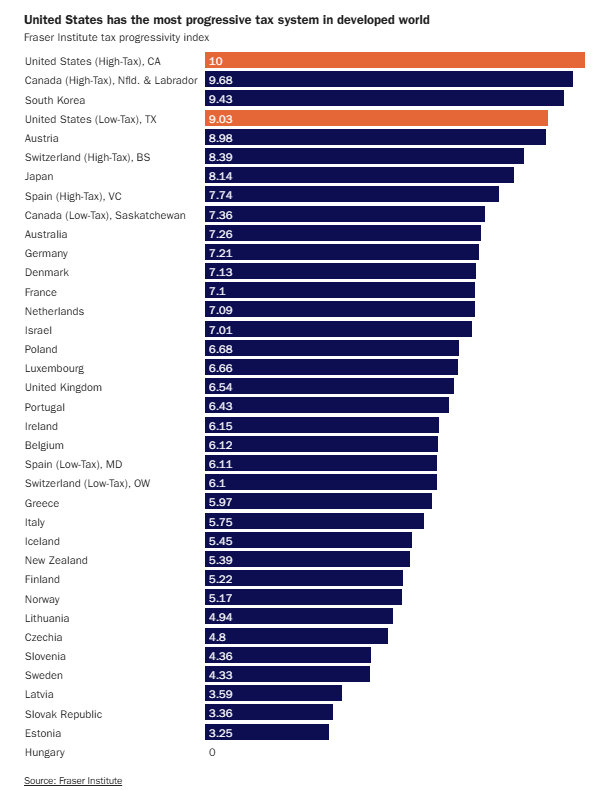

Bipartisan Fiscal Forum (BFF) introduces 3% Deficit Target Resolution. In a new resolution, the BFF cites the following among other reasons for adopting this resolution: “rising deficits and debt represent a threat to national security, economic growth, and future generations. […] rising deficits also threaten to increase interest rates and the cost of living, reduce the government’s flexibility to respond to fiscal emergencies, and create risks of a fiscal crisis.” The prescription of the resolution is “a fiscal target to reduce the Federal budget deficit to 3 percent of gross domestic product (in this resolution referred to as “the target”) or less as soon as possible and no later than the end of fiscal year 2030.” If Congress wants to take such a resolution seriously, they should implement a BRAC-like fiscal commission to implement the changes necessary to reduce federal deficits. As Boccia explains: “A BRAC-like fiscal commission could be tasked with addressing America’s alarming fiscal trajectory, including through Social Security reform. Its defining features, insulation from politics and fast-track authority, give it a far greater chance of succeeding where previous commissions with similar goals have failed.”

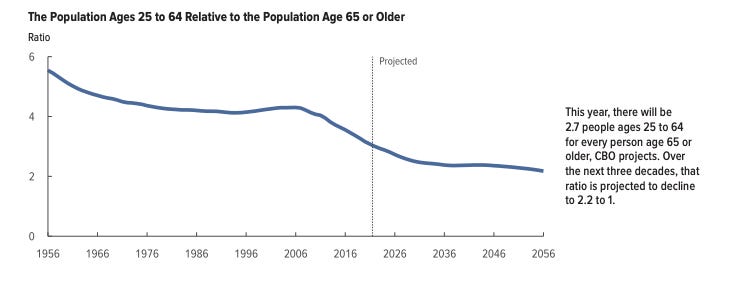

Spending increases fueled by tariff revenue delusion continue: this time for increased military spending. President Trump recently claimed that the defense budget should increase from $1 trillion to $1.5 trillion a year due to tariff revenue. Cato’s Scott Lincicome and Alfredo Carrillo Obregon point out how this is another installment in the fantasy of tariff revenues: “Trump has claimed in the last 15 months that tariffs could pay for eleven federal government policies or programs. Some have already been funded through regular congressional appropriations and general revenues, of which tariffs remain a relatively small part. The rest of these initiatives remain on standby because they’d require legislation from Congress.” CRFB estimates that this increase in military budget adds “$5.8 Trillion to the debt over the next decade”. The chart below shows how tariff revenue is nowhere near the amount necessary to pay for this spending increase.

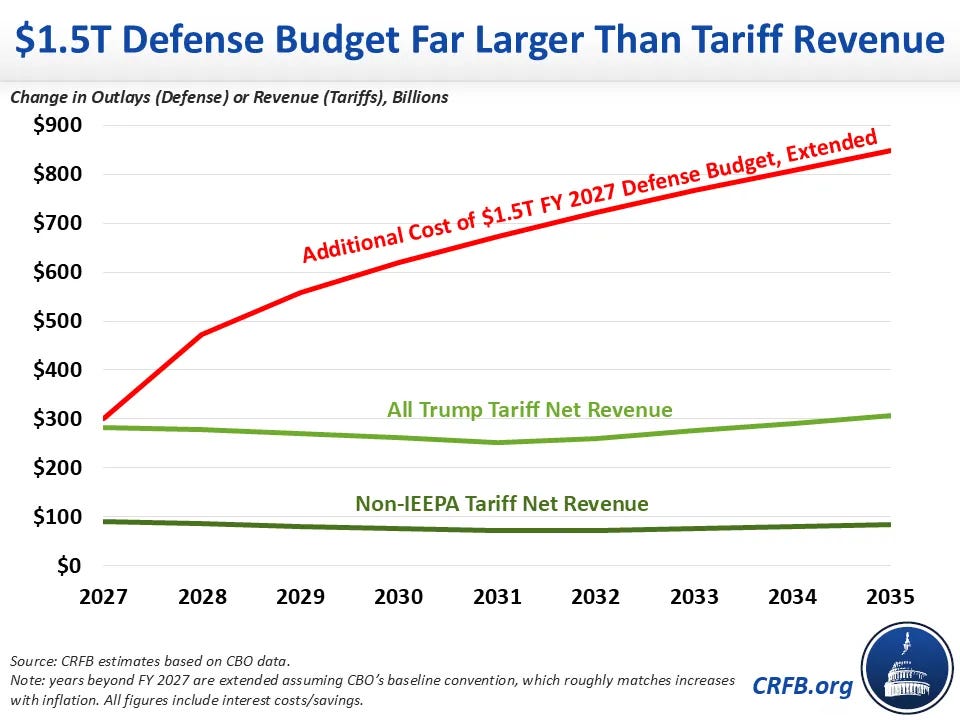

The US tax system is the most progressive in the developed world. Adam Michel explains in Cato at Liberty: “Taking a simple average of the highest- and lowest-progressivity states or provinces, the United States as a whole outranks every other country. [see figure below]” The reason for this result: “The federal income tax is highly progressive, with a relatively low marginal rate of 10 percent for lower-income filers and a top rate of 37 percent for higher incomes. Combined with the absence of a broad-based national consumption tax (like a value-added tax), the result is a highly concentrated tax burden on the highest-income Americans.” Michel continues, “We can sustain this structure largely because overall US tax levels are relatively low. Taxes as a share of GDP in the US are almost ten percentage points lower than the European average.” He concludes, “the lesson from the rest of the world is that high spending requires less progressive tax systems and high taxes on the poor and the middle class, not just the rich.”

Gold rise is a warning for the US dollar. Ray Dalio notes that “rising gold prices reflect a weakening economy and a national currency that is decreasing in value.” The implications of this trend: “When one’s currency goes down, it reduces one’s wealth and one’s buying power, it makes one’s goods and services cheaper in others’ currencies, and it makes others’ goods and services more expensive in one’s own currency.” Cato’s Jai Kedia echoes this reasoning, as well as “the jeopardy to the USD’s status as the world’s reserve currency.” Kedia outlines the consequences: “The USD and financial products denominated in dollars, such as Treasury securities or corporate bonds, are the safe asset of choice for investors from around the world. The benefit to the US is that private firms and the government alike can rely on such demand to fund their usual operations and projects. If foreign investors are concerned about losing money when exchanging their own currencies for the USD, their appetite for US financial products could fall, lowering US asset prices.”