Here are this week’s reading links and fiscal facts:

Sweden is not socialist. The Cato Institute’s Johan Norberg writes, “Public spending [in Sweden] is a bit higher than America’s, but not dramatically so. According to the latest OECD data on general government spending, Sweden spends 49.1 percent of GDP compared to 44.9 percent in United States. Social spending is very similar, 23.7 and 22.7 percent of GDP respectively.” Moreover, Sweden has no taxes on property, wealth, gifts, and inheritance while simultaneously having lower corporate tax rates than other OECD countries. “If America is not an example of socialism, it is difficult to make the case that Sweden is.”

Foreign ownership of US public debt declines. Chelsey Dulaney and Megumi Fujikawa write in the Wall Street Journal, “Foreigners no longer have an insatiable appetite for U.S. government debt. That’s bad news for Washington…Foreigners, including private investors and central banks, now own about 30% of all outstanding U.S. Treasury securities, down from roughly 43% a decade ago.” “Meanwhile, supply [of federal debt] has exploded. The U.S. Treasury has issued a net $2 trillion in new debt this year, a record when excluding the pandemic borrowing spree of 2020.” “The foreign ownership of Treasurys continues to decline and we expect that will remain the case for the foreseeable future,” says Praveen Korapaty, chief interest rates strategist at Goldman Sachs. This development means the US government will have to rely more heavily on domestic bond buyers to finance large-scale deficits, with higher interest rates here to stay, unless the Federal Reserve steps in with more quantitative easing to finance excessive and growing government spending. The latter risks driving up inflation. The only way out is for Congress to rein in automatic spending growth by reforming entitlement programs. A commission designed after BRAC stands the greatest chance of breaking through the gridlock foreboding a destructive debt doom cycle.

Old-age entitlements are not self-financed. “For a single male earning an average wage every year and who retired in 2020 at age 65, lifetime Social Security and Medicare benefits would equal about $640,000, while total taxes paid would be just shy of $470,000. For a couple with one average earner and one low-wage earner, benefits would total about $1.24 million, while taxes would reach $680,000.” write Tax Policy Center’s Gene Steuerle and Karen Smith. “The imbalance between taxes paid and earnings received is expected to increase…The consequences [of this imbalance] are reflected in both higher government-wide deficits and a smaller share [of] outlays dedicated to other programs.” 95 percent of all long-term unfunded obligations are due to rising spending on Medicare and Social Security. Entitlement reform must happen and soon.

Defusing the debt bomb. Romina presented on the rapidly deteriorating US fiscal decline for the Free Market Institute at Angelo State University (see the video below). High debt matters now for economic growth, not just because it could trigger a more severe fiscal crisis in the future.

Can economic growth save Social Security? Short answer: no. Several Republican candidates, including Ron DeSantis and Vivek Ramaswamy, have claimed that the US can “grow” its way out of coming Social Security insolvency by boosting economic growth to 3 to 5 percent per year. As the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget explains, “[higher economic growth usually comes with] wage increases [which] would result in higher benefit payments over time, as initial benefits are based upon wages and the benefit formula is indexed to wage growth. Furthermore, because the trust fund is only a decade from exhaustion and faces such a large shortfall, even a substantial boost in growth would only slightly delay trust fund depletion. Indeed, the Social Security Trustees have estimated that a 50 percent increase in real wage growth would only delay Social Security’s insolvency date by one year.”

Tax increases won’t bring fiscal sustainability. In a new paper, Kimberly A. Clausing and Natasha Sarin propose a menu of revenue-raising tax reforms that would generate $3.5 trillion over the coming decade, “stabilizing debt-to-GDP ratios at current levels over the coming decade.” While they highlight a few revenue proposals worth considering, the main problem with a tax-focused approach to primary balance is spending consistently outstrips revenue. Since 1970, revenue has exceeded outlays in only four years (1998—2001). What we’re witnessing time and time again is higher revenues end up chasing yet higher spending. As the Tax Foundation explains: “While tax revenue has increased about 28 percent since the pre-pandemic year 2019, spending has increased about 46 percent, and the deficit has more than doubled to $2 trillion.” Moreover, “If higher taxes have even a modest negative impact on growth, tax increases have no capacity for restoring fiscal balance. That finding leaves expenditure cuts—especially to Medicare, Medicaid, and ACA subsidies—as the only viable avenues for significant reductions in fiscal imbalance,” explains Jeff Miron.

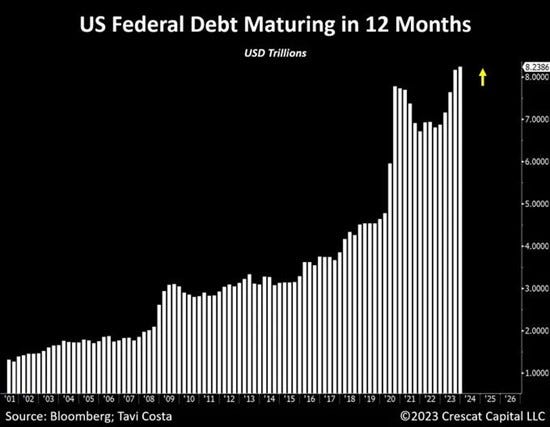

Hungry Uncle Sam. “The amount of refinancing Uncle Sam needs continues to grow, with more than $8T of debt maturing in the next 12 months,” writes Moses Sternstein. That’s 1/3 of total Treasuries outstanding and 3.5x more than what was net issued this year. Consider also the additional $2 trillion net-new issuance next year to cover the projected deficit. “That’s a whole lot of borrowing at precisely the time when central banks, especially ours, have said ‘borrowing money is going to be hard and expensive.’” See the graphic below showing federal debt maturation over time.