Here are this week’s reading links and fiscal facts:

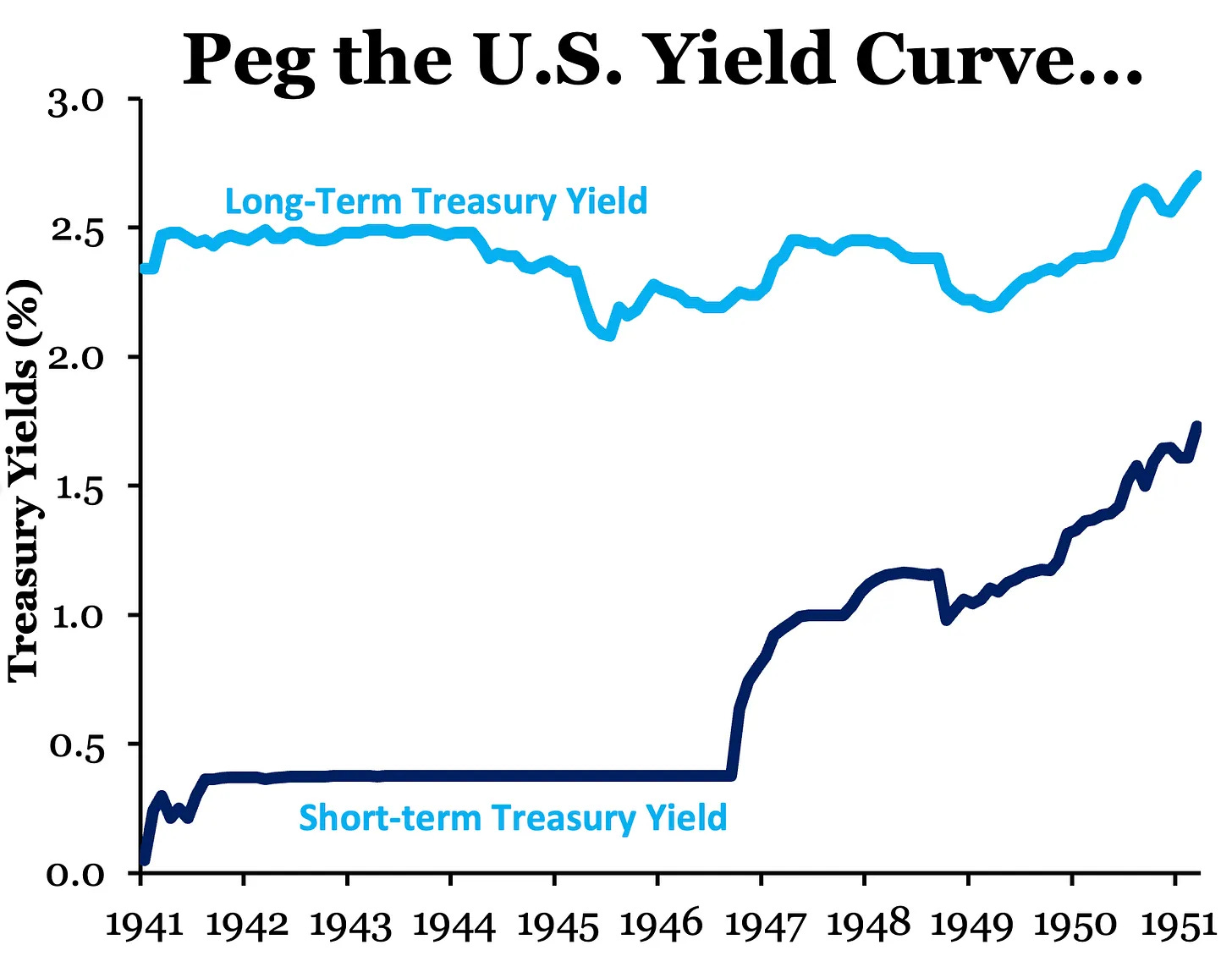

Fiscal irresponsibility threatens fiscal dominance. Mercatus Center’s David Beckworth explains how fiscal policy dominated monetary policy during World War II: “From 1942 to 1951, the Fed operated under an explicit agreement with the Treasury to cap interest rates across the yield curve to support wartime financing. Short-term rates were held at ⅜ percent, and long-term rates were pegged at 2.5 percent [see figure below].” He warns: “What’s different now is that the fiscal picture is deteriorating absent any comparable emergency. The risks of fiscal dominance today stem not from a temporary shock, but from rising structural deficits and a political system that shows little appetite for course correction.” Beckworth concludes: “[U]ntil we confront the growing costs of Social Security, Medicare, and other structural drivers of the deficit, it will be difficult to avoid drifting into a regime of fiscal dominance — not because of a crisis, but because the math leaves us with no other way out.” Read more in this blog by Boccia and Dominik Lett on the inflationary threat of fiscal dominance.

Counterproductive federal employment rules undermine government effectiveness. Sahil Lavingia reflects on his time as a software engineer at the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), where he was assigned to the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). He was surprised by the “brutally deterministic” workforce reduction rules, which prioritized protecting tenured employees and targeted new hires, regardless of their performance ratings. “These reduction-in-force rules–which stem from the Veterans' Preference Act of 1944–surprised me and many others. Unlike private industry layoffs that target middle management bloat and low performers, the government cuts its newest people first, regardless of performance,” writes Lavingia. These rules reflect special interest influence, particularly from public sector unions, which have historically lobbied for rigid seniority protections. While designed to shield workers from political retaliation and unfair treatment, these provisions limit management flexibility and prioritize tenure over talent. He also notes that DOGE didn’t directly control firings: “The real decisions came from the agency heads appointed by President Trump, who were wise to let DOGE act as the 'fall guy' for unpopular decisions.” For broader reasons why DOGE failed to generate significant savings, see this BBC interview with Cato’s Alex Nowrasteh.

A bipartisan bill to help retirees make more informed decisions. Mercatus Center’s Charles Blahous, a former trustee for Social Security and Medicare, addresses a widespread misconception: that Social Security’s full retirement age (FRA) of 67 is the earliest age at which one can claim benefits. In reality, individuals can claim benefits at the early eligibility age (EEA) of 62, while the FRA delivers an arbitrarily defined “standard benefit.” He points to a bipartisan bill by Senators Cassidy (R-LA), Coons (D-DE), Collins (R-ME), and Kaine (D-VA) that would rename existing thresholds: age 62 as the “minimum monthly benefit age,” 67 as the “standard monthly benefit age,” and 70 as the “maximum monthly benefit age.” Blahous argues: “Americans need to understand that under current law they can claim old age at any age from 62 on, and that their choice can minimize or maximize their benefit, or be somewhere in between. Americans can best plan for their retirement if they have an accurate understanding of what they will get from Social Security and when.”

The growth effects of the GOP bill are a mirage. A recent Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) report finds that the GOP’s reconciliation bill would increase the average annual growth rate of GDP by just 0.03 percentage points over the next ten years. This would generate $103 billion in additional revenues, much lower than the $2.5 trillion assumed by the House. As Kent Smetters, faculty director of the Penn Wharton Budget Model, explains, this is partly because pro-growth provisions like full expensing of capital and R&D investments are temporary, making the short-term growth effects “a bit of a mirage.” The final reconciliation bill should make these provisions permanent while scrapping tax subsidies, such as the state and local tax (SALT) deduction and the exemption of tips and overtime pay from taxes. To further boost economic growth, the bill should minimize its deficit impact by adopting larger spending reductions.

The one big bloated bill. Economist Scott Sumner offers a scathing summary of the House’s reconciliation bill: “This tax bill is almost unimaginably bad. If you are a progressive it’s bad because there are massive tax cuts for the rich while the poor are hit by tariffs and benefit cuts. If you are a supply-sider the bill is bad because it reduces economic efficiency. The SALT deduction alone is an engine for massive wasteful spending in high tax states. If you like simplicity the bill is bad because it makes the tax system far more complex—we are back to itemizing deductions. I don’t think even Kamala Harris would have produced something quite this bad, and any other GOP president would have delivered a far better bill.” Boccia recently called it “the one big bloated bill” and criticized its provisions like the SALT, pointing to the need for more meaningful spending cuts and tax loophole reforms.