Here are this week’s reading links and fiscal facts:

Early action will define the new administration’s success. Michael Magoon, author of the "From Poverty to Progress" book series, highlights the rules and dynamics surrounding presidential power, including that a new President has only a 15-month window to advance a legislative agenda until Congress shifts its focus to midterm elections. Magoon argues that in domestic policy, a president’s main power lies in setting the legislative agenda: “There are always hundreds of different issues that the federal government can focus on, but only a few of them can be dealt with at any one time. The President has real influence in determining which of those issues are on the current legislative agenda, particularly in his first year in office.” The Trump Administration should consider a comprehensive fiscal strategy to extend pro-growth tax cuts and put the budget on a path to balance. Without tackling unsustainable spending, the Administration and Republican Congress risk fueling runaway inflation and voter backlash.

Repeal the Inflation Reduction Act. Our Cato colleagues, Travis Fisher, Adam Michel, and Joshua Loucks argue that Congress should repeal the misleadingly named Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and use the savings to partially offset extensions of the expiring 2017 Trump-era tax cuts. Michel, Fisher, and Loucks write “The energy and climate provisions of the IRA are already burning through taxpayer dollars at rates much higher than initially projected. These subsidies will likely cost over $1 trillion by 2032 and as much as $4 trillion by 2050, and some of the most lucrative tax credits have no expiration date.” Beyond the fiscal impact, these subsidy tax credits create deadweight losses from rent-seeking and distort markets: “Attempts to centrally plan markets through subsidies or other industrial policies will stifle true innovation and limit prosperity because many productive entrepreneurs will become subsidy harvesters.”

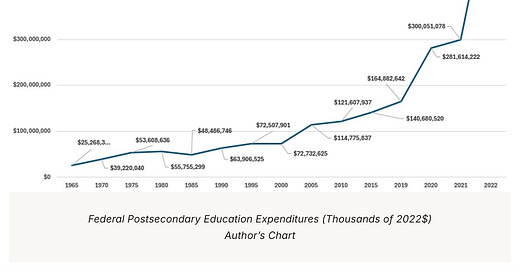

End federal involvement in education. Cato’s Neal McCluskey highlights that since 1965, inflation-adjusted federal spending on education has surged from $25 billion to $620 billion (see figure below). Even excluding COVID-related spending, a major source of this increase, education spending grew seven times between 1965 and 2019. McCluskey argues this has led to more degrees but declining quality: “[T]he federal government incentivizing people to go to college has increasingly flooded the market with pieces of paper that represent less and less learning, and that do less to distinguish one potential employee from another.” He also notes that spending on student loans has decreased from its peak in 2011, indicating that students are more reluctant to take excessive debt for expensive education, prompting many schools to lower their prices. However, federal loan cancellation efforts may weaken these market forces. McCluskey concludes: “We would all be better off with a leaner, more efficient higher education system. To do that, we must get the feds out.”

Reason’s J.D. Tuccille quotes me on Social Security. “[…] Social Security is and always has been a scam that is rapidly approaching collapse,” writes Reason’s J.D. Tucille. He references my new policy report, where I debunk myths around Social Security’s trust fund: “Boccia reminds us that the famous Social Security ‘trust fund,’ which many Americans wrongly believe contains money paid into the program to be disbursed at a later date, doesn't really exist. ‘The trust fund essentially consists of IOUs or promissory notes that represent claims on future tax revenues.’” Tuccille highlights that private savings outperform Social Security for everyone except for the poorest, which suggests Social Security should be focused on keeping those individuals out of poverty. He concludes: “Americans should prioritize planning for their own futures rather than relying on a nonexistent "trust fund" made up of nothing but debt and empty promises.”

Spending cuts for 2025. Cato’s Adam Michel and Chris Edwards propose 14 recommendations for spending cuts that would save $4.8 trillion over ten years. These include reducing federal employee retirement benefits, currently 47 percent higher than what similar workers from the private sector receive, which can save $237 billion in the next ten years. They also suggest rolling back the SNAP increase ($190B), tightening welfare work requirements ($171B), ending categorical eligibility ($112B), cutting junk food subsidies ($1T), restricting welfare for immigrants ($1.3T), ending student loan forgiveness ($22B), capping federal student loans ($185B), reducing ACA tax credit abuse ($44-$95B), stopping Medicaid financing gimmicks ($500B), converting Medicaid to a block grant ($600B), expanding site-neutral Medicare payments ($100B), limiting bad Medicare debt reimbursements ($23-$74B), and selling Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac ($240B). Michel and Edwards argue that cutting spending isn’t bad politics, stating: “A far larger political risk for the Republicans is if they don’t cut spending and deficits, and inflation spikes again over the next two years.”

Awesome. Thanks for your work!

I find it strange that into a mix of mostly pragmatic suggestions you include one - get the federal government entirely out of education - that is hopelessly unrealistic.

Certainly in the current environment with the current president.

It seems to me there are numerous other improvements- and cost savings - to be made re federal education spending than one which we classical liberals and debt hawks would love (eliminate federal education spending altogether) which has absolutely zero chance of occurring any time soon.

If you’re gonna make that particular case, it should be done imo in a standalone piece, not combined with much more pragmatic points.