Here are this week’s reading links and fiscal facts:

Creating a US sovereign wealth fund is not a good idea. Mercatus Center’s Tyler Cowen discusses the idea of a US sovereign wealth fund (SWF), considered by both Former President Trump and President Biden. Cowen notes that successful SWFs in countries like Singapore, Norway, and the United Arab Emirates share a key feature: “[T]hey typically run a surplus in their government budgets.” In contrast, the United States runs budget deficits, meaning it would need to borrow to fund the SWF. Cowen argues that even if the fund returns exceed borrowing rates, it won’t increase net social value: “On paper, the sovereign wealth fund looks like a big success, but the government has simply issued more debt and redistributed some equity returns away from the citizenry and toward itself.” Cowen warns: “If the US SWF bought significant percentages of domestic companies, it would essentially bring the US a kind of socialism, with extensive government ownership of the economy.”

CBO’s budget baseline is flawed. Mercatus Center’s Charles Blahous, a former public trustee for Social Security and Medicare, critiques the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO’s) scorekeeping baseline that assumes Social Security and Medicare will continue paying scheduled benefits even after their trust funds are exhausted, which contradicts current law. Blahous writes: “[T]his difference between the scorekeeping baseline and current law is enormous, because Social Security and Medicare benefit schedules currently exceed projected financing by trillions of dollars [...]” He adds: “The baseline assumes this spending growth despite the fact that there is no legal authority for much of it. [...] This assumption severely biases budget outcomes in the direction of perpetually rising spending [...] At the same time, the scoring system inconsistently assumes current tax rates will expire, implicitly accepting higher future tax burdens.” Similar to my proposal for the CBO to produce an alternative baseline that does not unrealistically assume the expiration of tax cuts, Blahous suggests a CBO alternative baseline should reflect reduced Social Security and Medicare benefit payments after their trust funds are exhausted.

Remove emergency spending from the budget baseline. At a recent congressional hearing, Congressman Glenn Grothman (R-WI) questioned CBO director Dr. Phill Swagel about the rationale for extending $95 billion in the temporary emergency aid to Ukraine, Israel, and Taiwan over the 10-year budget window, which increased the budget baseline by $900 billion. Dr. Swagel responded: “ We look at it the same way as you do [...] This looks like it’s one-time money [but] by statute we are required to extend it.” As Dominik Lett and I’ve written before, this statute, which requires the CBO to treat temporary emergency spending as permanent, “creates an insidious ratcheting effect, baking in a bias towards higher spending. Spending-prone legislators can point to the artificially elevated baseline to justify further spending increases. Moreover, it undermines the original purpose of emergency spending—a budgetary safety valve for necessary, sudden, urgent, unforeseen, and not permanent situations.” Congressmen Grothman and Ed Case (D-HI) have introduced the Stop the Baseline Bloat Act (H.R.8068), which would remove emergency spending from the budget baseline. As we’ve noted, “This change would make CBO's baseline less biased towards higher spending.”

Explore how inflation has affected your costs with the Personal Inflation Calculator. The Heritage Foundation recently released the Personal Inflation Calculator, an interactive tool that shows the impact of inflation on personal finances. By entering your monthly expenditures on categories like groceries, electricity, gasoline, and restaurants, you can see how inflation has driven up your costs compared to reference years (2017-2023). In addition, the calculator allows you to filter for your location, providing more accurate results tailored to your place of residence. For example, an urban worker living in New York City is paying $2,620 in monthly expenses on average, $419 more than in September 2020, a 19 percent increase over four years. As Heritage explains: “Prices are rising because of the federal government’s reckless spending, paid for by printing new money that devalues your dollars. It acts like an invisible tax.“

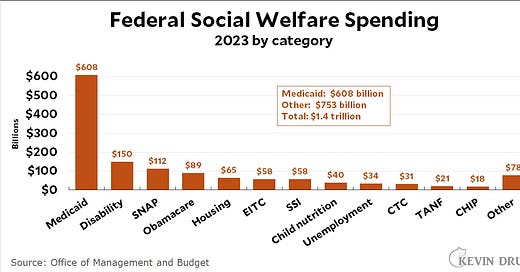

Healthcare programs and Social Security—not welfare spending—are the main contributors to long-term federal debt. Phil Gramm, a former chairman of the Senate Banking Committee, and Rep. Jodey Arrington (R-TX) argue that Social Security and Medicare are not the primary drivers of federal deficits and debt. They write, “The real driver, the elephant in the room, is means-tested social-welfare spending—Medicaid, food stamps, refundable tax credits, Supplemental Security Income, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, federal housing subsidies and almost 100 other programs whose eligibility is limited to those below an income threshold.” While highlighting the fiscal burden of welfare spending and related socioeconomic issues is important, their argument is somewhat misleading. The key problem is lumping Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) together with other welfare programs. As shown in the graphic below, these two programs make up nearly half of all federal welfare spending. It would be more informative to focus on healthcare spending relative to other budget categories, as healthcare has been the main driver of federal debt over the past 50 years. As Charles Blahous explains: “The entirety of the overall federal spending increase relative to GDP over the long term can be accounted for by the growth in the major federal health programs (Medicare, Medicaid, and the ACA) and Social Security.” Furthermore, as I’ve pointed out before, Medicare and Social Security’s long-term funded obligations make up 100 percent of the US government’s unfunded obligations over the next 75 years.