Here are this week’s reading links and fiscal facts:

Designing effective spending caps. The recent debt limit deal imposes two years of statutory caps on discretionary appropriations. Backdoor deals and budgetary gimmicks likely mean major savings will not be realized. In a historical lookback at US discretionary caps, the Manhattan Institute’s Brian Riedl found that “discretionary caps can constrain spending. The past 44 years have split evenly between 22 years with caps and 22 years without them. Average annual appropriations went up 2.7 percent during capped years, versus 6.4 percent during uncapped years.” Read the full report here.

Reviewing Biden’s Social Security track record. Biden has repeatedly attacked Republicans for proposing Social Security reforms despite having advocated for similar reforms decades earlier. Bipartisanship will be crucial to prevent indiscriminate benefit cuts in 2033. According to AEI’s Andrew G. Biggs and James C. Capretta, “Biden himself should know this – he was directly involved with one bipartisan compromise” that raised the retirement age to 67, made Social Security benefits subject to income taxes, and delayed cost-of-living adjustments (COLA). As Boccia points out, the Republican Study Committee’s proposals to increase the retirement age to 69 and reduce benefits for the highest income earners are good places to start.

De-dollarization? Not so fast. Stanford economist Jonathan S. Hartley writes, “[E]ven after events like the globally destabilizing COVID-19 pandemic and the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the U.S. dollar seems no less prevalent in the invoicing of trade, [holdings of] central bank currency reserves, foreign exchange transaction volume, and…global debt securities.” Cato’s Daniel Griswold and ECIPE’s Andreas Freytag concur: “For the nation as a whole, the strength of the dollar reflects the continued attractiveness of the United States as a relatively stable haven for global savings.” In the long run, unsustainable debt increases the likelihood of a sudden fiscal crisis which could undermine US dollar dominance. Read Boccia’s analysis here.

Waste and fraud from pandemic spending spree grows. The Associated Press found that fraudsters potentially stole more than $280 billion in COVID-19 relief funding with another $123 billion being wasted or misspent. “Combined, the loss represents 10% of the $4.2 trillion the U.S. government has so far disbursed in COVID relief aid. That number is certain to grow as investigators dig deeper into thousands of potential schemes.”

Emergency spending needs responsible accounting. Current emergency designations allow Congress to enact spending or revenue changes even if doing so would violate budgetary enforcement rules. Likewise, emergency spending or revenue changes have no effect on the budget enforcement of regular, non-emergency provisions. Including direct spending in response to the pandemic, Congress has spent about $6 trillion for emergencies over the last 5 years. “Congress could adopt notional emergency spending accounts to track supplemental appropriations and enforce offsetting spending reductions,” Boccia argues. R Street’s Jonathan Blydak spotlights several other methods to curb emergency spending, such as narrowing the definition of emergencies and creating a “rainy day” federal emergency fund.

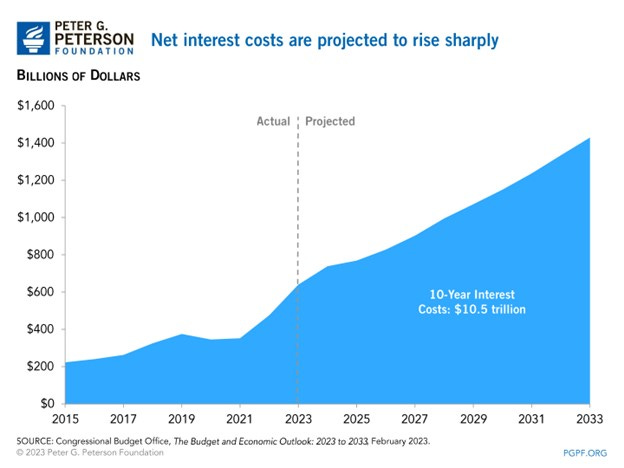

Fiscal challenges await the next administration. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget highlighted key upcoming fiscal challenges. In 2025, recently enacted statutory caps will expire. Likewise, temporary Trump-era tax cuts and pandemic-era health care subsidies will expire the same year. By FY 2027, interest costs are projected to exceed total defense costs. By FY 2028, the Highway Trust fund will run out of reserves with Medicare (2031) and Social Security (2033) insolvency just around the corner. By FY 2029, debt held by the public will exceed the previous WWII record, reaching 107 percent of GDP. Read more about budget projections here.

Interest costs total $10.5 trillion over the next decade. The Peterson Foundation underscored key drivers of the federal debt. “Federal spending — driven by rising healthcare costs, demographics, and interest payments on the national debt — is paired with revenues that are insufficient to meet the commitments that have been made.” The chart below shows the rapid growth in projected interest costs over the next 10 years.