Here are this week’s reading links and fiscal facts:

End automatic tax withholding. Cato’s Adam Michel critiques the practice of automatic tax withholding and explains why we shouldn’t be celebrating a Tax Day refund: “[Y]our refund is simply the US Treasury’s return of money you overpaid throughout the year — the result of a series of interest-free loans you unwittingly made to the federal government.” He notes that automatic withholding enabled the expansion of the income tax as it masked the impact of tax hikes. On the flip side, tax refunds can make tax cuts harder, as smaller refunds may lead taxpayers to overlook that they’re paying less overall. “Even though 80% of taxpayers sent on average a couple thousand dollars less to Washington [after 2017 Trump tax cuts], only 17% thought they’d gotten a tax cut — proof that many Americans gauge their tax burden not by how much they pay throughout the year, but by the size of their refund,” explains Michel. He concludes: “Tax Day should trigger a moment of reflection, not a refund celebration. If we want democratic oversight of fiscal policy, we must stop hiding the bill.”

A trade deficit is an investment surplus. Tax Foundation’s Erica York explains: “Rather than reflecting the practices of foreign nations, the trade deficit primarily represents our decisions about how much to save (or spend) versus invest. In economic terms: saving minus investment equals exports minus imports. The nearby chart [see below] illustrates the resulting mirror image. Year after year, our trade deficit is matched by a surplus, or inflow, of foreign investment. [...] The next time you hear a politician complain about the trade deficit, remember that it isn’t an economic scorecard between nations. Instead, it’s the result of choices we make as a nation about saving, spending, and investing.” As we’ve noted in a previous edition of Debt Digest, because trade deficits and capital surpluses are two sides of the same coin, President Trump’s push to lower the trade deficit while encouraging foreign investment is inherently contradictory.

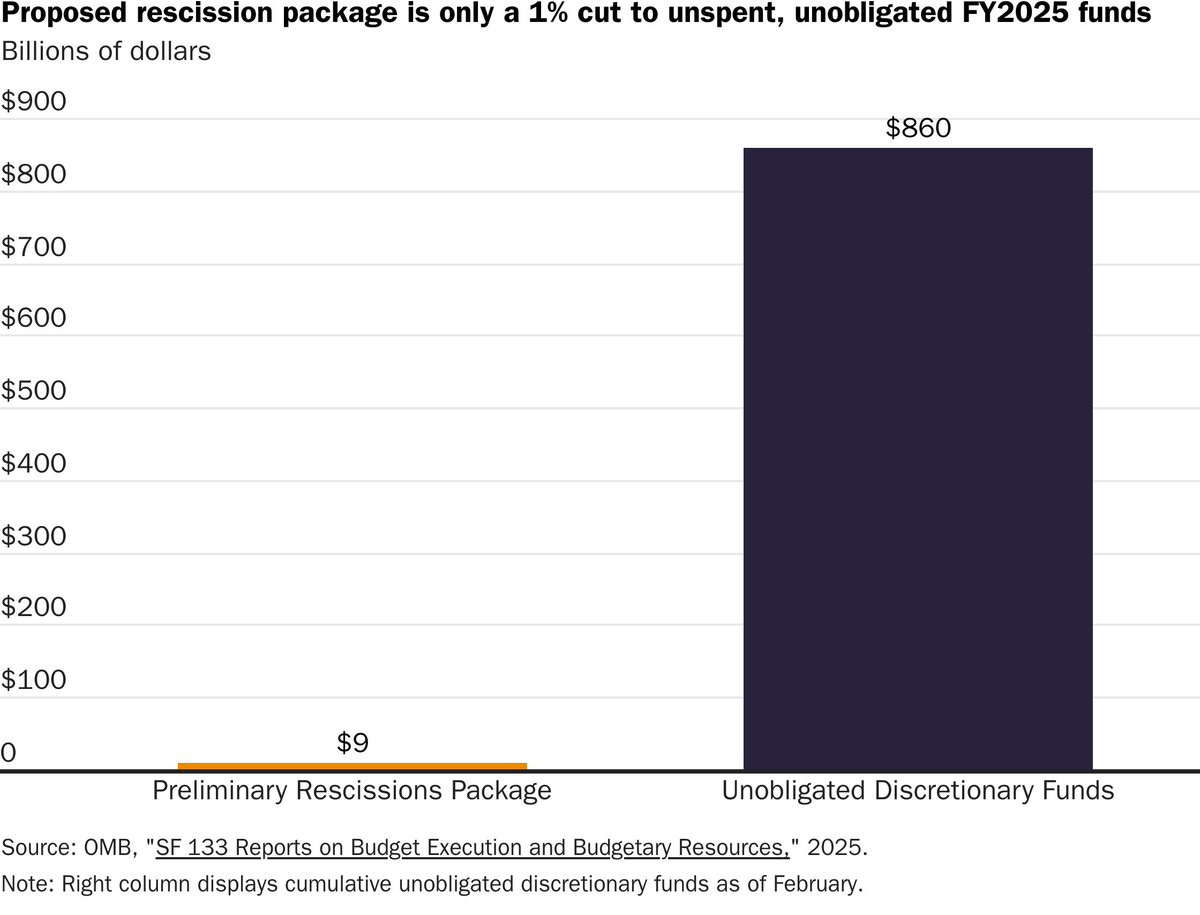

The White House’s rescission package is a good start—but far too small. David Stockman, former OMB director under President Ronald Reagan, writes: “[W]hat the DOGE team needs to do right now is bundle-up a massive pile of rescissions and send them to Capitol Hill to be approved as a pre-condition for passage of the next CR. We think there is enough fraud, waste and abuse based budget authority lying around the Federal bureaucracy such that a massive $600 billion rescission package could be sent to the Hill [...].” While the White House is reportedly planning a $9.3 billion rescission package, Dominik Lett points out that this amounts to just 1 percent of FY 2025’s $860 in unobligated funds (see figure below). If the new administration is serious about cutting spending, it should send much larger rescission package(s) to Congress. As Boccia and Lett have noted: “The administration could break these rescission requests into multiple smaller packages, following the agency-by-agency approach of DOGE, or they could submit a single, comprehensive rescissions package covering a wide array of policy areas.”

Medicaid is poorly targeted, and its cost growth is unsustainable. Mercatus Center’s Charles Blahous warns that Medicaid’s cost growth has been outpacing economic growth: “This can’t go on forever, which means the question is not whether to slow Medicaid’s cost growth but how.” He explains that the federal government provides higher reimbursement rates for the Affordable Care Act (ACA) expansion enrollees, who are nonaged, able-bodied adults above the poverty line. “There is no health policy reason why the federal government should pay far more of the costs of covering a higher-income, nonaged, able-bodied, childless adult than it does for covering a pregnant woman living in poverty,” writes Blahous. He highlights Paragon Health Institute’s proposal to equalize reimbursement rates and move those above the poverty line out of Medicaid, which could save over $250 billion over 10 years. Blahous also points to reforms like ending the provider tax scam and curbing improper payments, concluding: “Lawmakers should be applauded rather than demonized for confronting the rising costs of Medicaid.”

When debt is high, more government spending can reduce economic output. Mercatus Center’s Jack Salmon recently conducted a literature review examining the estimates of the fiscal multiplier—the measure of how much an additional dollar of government spending affects GDP. The estimates of government spending multiplier generally fall between 0.5 and 0.9, meaning each dollar of government spending generates less than one dollar in economic output. Importantly for the United States, research shows that multipliers are lower for countries with higher debt levels. “[H]igh-debt regimes typically have multipliers between 0 and 0.40,” writes Salmon and cites several studies that point to negative multipliers in the long term. For example, one study found that “for high-debt countries (debt ratio around 105 percent), the multiplier reverts back to zero and then turns negative (less than –1.00) after about two years.” These findings suggest that in a high-debt nation like the United States, additional government spending may do little to boost GDP and could even shrink it over time. Conversely, as Boccia and Lett have highlighted, reducing federal spending can boost economic growth.