Here are this week’s reading links and fiscal facts:

Fiscal commission can prevent a debt crisis. “This nation is slouching into the most predictable fiscal crisis in its history,” writes George Will. “Without politically excruciating changes, the two principal drivers of federal deficits — Social Security and, especially, Medicare — will produce ever-higher government spending and ever-larger deficits…Adopting Boccia’s recommendation — ‘a new mechanism for forcing action’ — would be an admirable acknowledgment by Congress of an unadmirable weakness.” Read more about Boccia’s proposal for a BRAC-like fiscal commission here and here.

The Fed effect on government debt. Fitch Ratings downgraded the U.S. debt due to a growing government debt burden and the erosion of governance. “We’re experiencing a slow-motion fiscal train wreck, not a “soft landing,” and it’s draining global capital and endangering the dollar,” writes David Malpass, former President of the World Bank Group. While most of the focus is on Congress, the Federal Reserve is partly to blame. “Its more than $7 trillion in bonds support Washington’s deficit spending by holding down bond yields, blurring the line between fiscal and monetary policy.” Boccia discusses the risks of the Federal Reserve supporting Washington’s spending addiction here in her review of George Selgin’s book, The Menace of Fiscal QE.

Emergency spending abuse. Former House Rep. Justin Amash writes, “Republicans & Democrats are already working out how to get around defense spending caps by using “emergency” funding. As said before, Biden got the biggest win in the “deal” with a debt limit suspension (unlimited borrowing for spending) until 2025. The rest is smoke and mirrors.” Amash is right about the Fiscal Responsibility Act falling short. But it’s not just defense spending caps that are being evaded. Boccia and I explain how emergency spending designations are being abused in non-defense appropriations here.

More savings on the table for House spending bills. While the Senate has passed its 12 annual appropriations bills (thanks in large part due to excess “emergency” spending which is exempted from budget caps), the House appropriations bills are delayed due to disagreements over funding. The Heritage Foundation’s David Ditch argues that the House bills thus far include some valuable spending cuts but leave other savings on the table. One example: $20 billion for disaster relief. “While there is understandable sympathy for people suffering from disasters such as hurricanes, a handful of states receive the vast majority of disaster funds. This means adding to the federal debt to give handouts to these states at a time when Uncle Sam is going broke and states are passing tax cuts.”

Spending growth drives deficits. The last time the federal budget was balanced, Clinton was President. While almost every portion of the budget has grown, Social Security and major healthcare programs like Medicare and Medicaid have grown the most. As Cato’s Chris Edwards explains, “[F]ederal spending has risen from 17.7 percent of GDP in 2000 to 24.2 percent estimated for 2023.” If policymakers had kept spending at the 2000 level of 17.7 percent of GDP or restrained spending to the annual average nominal GDP growth rate of 4.2 over the last 23 years, today’s budget would be balanced. “Unfortunately, actual federal spending grew at an annual average rate of 5.7 percent between 2000 and 2023.”

Do government models underestimate debt and spending growth? An updated American Enterprise Institute paper estimates that the debt-to-GDP ratio will reach 134 percent in 2032 and 263 percent in 2052, compared to CBO’s 115 percent and 189 percent, respectively. “In the official models used by the Treasury and the Social Security and Medicare Trustees for projections and policy analysis, many key variables—like interest rates—are assumed as a continuation of past trends…in our model, these variables are simultaneously determined by supply and demand, based on logical functional forms and deep parameter estimates from the literature or empirical analysis,” write Mark J. Warshawsky and John Mantus of the American Enterprise Institute and Gaobo Pang of Smart USA.

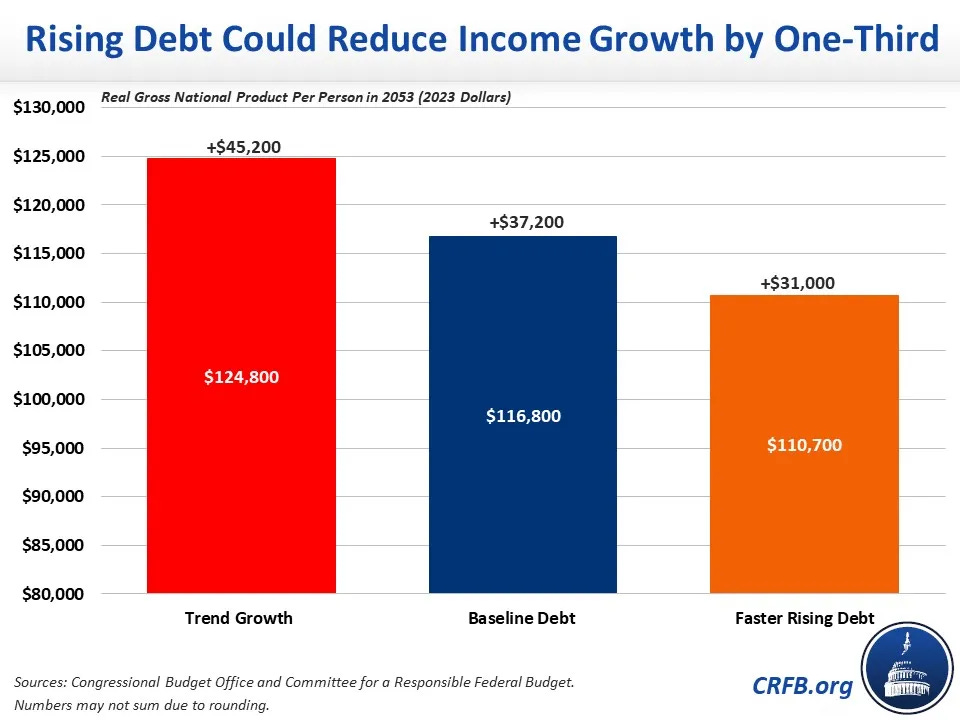

Federal debt reduces Americans’ income. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), before accounting for rising debt, annual average income is projected to grow by $45,200 per person over the next 30 years. Current projected debt growth reduces income growth by one-sixth, or $8000 per person in 2053. Under more realistic assumptions including spending hikes and tax cut extensions, debt reduces income growth by one-third, or $14,100. “In other words, faster rising debt would lower income growth by 31 percent and reduce total incomes by 11 percent in 2053,” Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget explains. See their graph comparing average income under different debt scenarios below. Boccia and I outline the high costs of debt here.

If the federal government did not have to finance a trade deficit of $945.3 billion, greatlty lowered defense spending of $766 billion, and did not waste an estimated $247 billion in taxpayer money each year, wouldn't that help balance the budget? Raising taxes may also be a good idea, maybe the best idea. Just transfer funds from those who already have enough to those who need it w/o government having to borrow to satisfy the need. Seems that everyone rebels against growing debt but nobody wants to do the obvious to reduce it. Not in my backyard.