Here are this week’s reading links and fiscal facts:

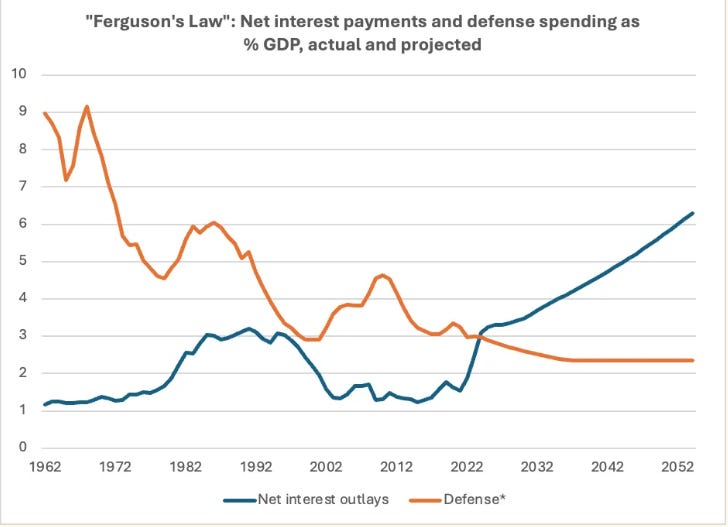

Spending more on interest than on defense is bad news. The Hoover Institution’s Niall Ferguson writes: “[...] I have suggested that when a great power spends more on debt service than on defense, it will not be great for much longer, a proposition that appears to be true of the Habsburg Spain, the Dutch Republic, Bourbon France, the Ottoman Empire, and the British Empire. (I have half-seriously called this Ferguson’s Law.) It should therefore be a cause for concern that the United States today, for the first time, spends more on interest payments on the federal debt than on national security [see figure below].” The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that net interest costs will more than double over the next 30 years, rising from 3.1 percent to 6.3 percent of GDP between 2024 and 2054. As more revenues are directed toward interest payments, fewer resources will be available for critical priorities like defense. Excessive peace-time deficits and debt also undermine America’s ability to borrow when it matters most, in times of crisis. Moreover, as we’ve written, “Higher interest costs reduce America’s relative international economic standing while making the United States government increasingly dependent on foreign and domestic creditors.”

We cannot continue ignoring the threat of a debt crisis. I recently joined Caleb Brown on the Cato Daily Podcast, where we discussed the dangers of unsustainable government spending and debt. I explained that while raising taxes could theoretically help address some portion of our fiscal challenges, it’s not a good idea, as doing so would require significant tax hikes that would stifle innovation and hurt America’s global competitiveness–it’s like shooting yourself in the foot. I also highlighted the threat of a sudden debt crisis, which could ensue due to the rising costs of servicing growing debt. To avoid these dire consequences, we need to agree on the path toward sustainable reforms, which must include addressing the growing burdens of Medicare and Social Security. Furthermore, I proposed establishing a BRAC-like fiscal commission of independent experts to help get critical reforms past the goalpost by giving legislators cover and thus overcoming political obstacles to implementation.

Ten programs DOGE should target. On Tuesday, President-elect Donald Trump announced the creation of the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE)—led by Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy—aimed at eliminating waste in government spending. Cato’s Chris Edwards suggests ten programs that the new executive commission “should put on the chopping block.” These include K‑12 public school subsidies, urban transit subsidies, foreign aid, green subsidies, broadband subsidies, public housing and rental subsidies, community development grants, junk food subsidies, farm subsidies for the rich, and reducing federal Medicaid costs. Edwards notes: “America risks a sustained economic crisis if we don’t cut federal spending. But cuts are also an opportunity to improve the nation’s governance and strengthen democracy by handing power back to the states.” According to Trump’s announcement, DOGE’s work should conclude by July 4, 2026. Yesterday’s Wall Street Journal article quotes Edwards, where he emphasized the importance of early wins: “[…] Edwards said Musk and Ramaswamy should go far beyond the idea of efficiency. ‘If they really want to cut spending,’ he said, ‘they need some modest-sized cuts and successes next year to give them the confidence that they can actually do these reforms and survive.’”

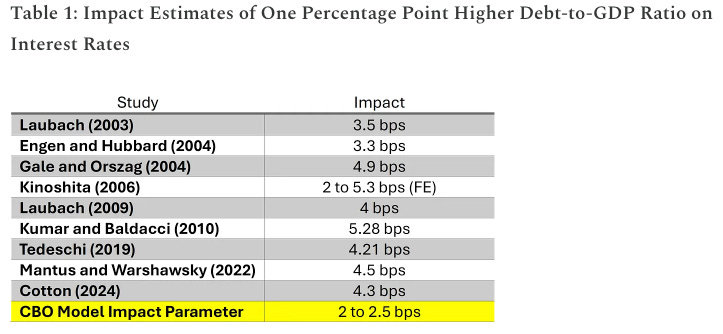

CBO underestimates borrowing costs. Jack Salmon, Director of Policy Research at the Philanthropy Roundtable, argues that the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) underestimates the effect of public debt on interest rates. This matters because as debt rises, it puts more pressure on interest rates to rise as well, which can trigger a debt doom loop where higher debt begets higher interest rates, begets higher debt…a vicious debt-interest cycle [listen to this Cato Daily Podcast to learn more]. Salmon explains that while the CBO assumes a 1 percentage point increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio raises interest rates by 2 bps, newer studies indicate a much stronger impact (see table below). He writes: “[The CBO] estimate seems well below the range of 3 to 5 bps commonly found in the literature and well below the 4 bps or higher estimates in the latest empirical studies. [...] This underestimation could lead to an overly optimistic view of future interest rate environments and the corresponding cost of borrowing.” Salmon previously published on how high levels of government debt reduce economic growth in a study for the Cato Institute.

Immigration helps Social Security. Robert Pozen, a senior lecturer at MIT Sloan School of Management, and Charles Blahous, a former public trustee for Social Security, challenge the misconception that immigration harms Social Security, stating: “[I]f future immigration were 35% higher than is now projected, Social Security’s financing shortfall would be reduced by 11%. Immigration can’t eliminate Social Security’s financing shortfall, but it helps.” They add that undocumented immigrants provide a higher net plus for Social Security’s finances than legal immigrants, as many pay payroll taxes through invalid Social Security numbers without ever becoming eligible for benefits. Beyond its positive effects on Social Security, immigration provides broader fiscal benefits. As we’ve covered in a previous Digest, the CBO estimates that increased immigration will lower deficits by $0.9 trillion over the next 10 years.

Remove the earnings cap on Social Security taxes, means test Social Security benefits. The federal government’s major fiscal problem is solved.

XXX